Setting the scene

Although concepts such as the rule of law and democracy are well embedded in the constitutional culture of the UK, the absence of a codified constitution creates considerable space for uncertainty as to how key aspects of public decision-making should be carried out. A major example was the dispute surrounding the process by which Article 50 of the Treaty on the European Union should be triggered.Such disputes would happen even with a written constitution in place, not should the degree of detail on the UK's constitutional arrangements be under-estimated. What we do have is an almost universally accepted commitment to Parliamentary Sovereignty, which as confirmed in the Miller case positions Parliament as the ultimate source of constittuional authority. This prinicple is supported by a series of institutions and conventions, as is perhaps most completely outlined in the Cabinet Manual. The courts have also played a key part in articulating some of the detail on the constitution.

The Political Constitution

The

political constitution can be used as a phrase to describe how the

constitution operates, or as an ideal-type/normative description as to

how governance should operate, with a particular underlying

understanding that the input of the judiciary into matters of governance

should be heavily limited. On the descriptive side, the UK constitution

has often been characterised as a customary constitution, based upon a

pragmatic evolution of the political practice of governance and relying

upon past practice for constitutional direction. Fearing a drift towards

a more heavily legal constitution - even the imposition of a written

constitution - in the late 70s JAG Griffith wrote his seminal article:

‘The Political Constitution’ (1979) 42 Modern Law Review 1,

which argued for the normative superiority of a political

constitution. Griffith argued strongly against a Diceyan interpretation

of the UK constitution, primarily because it promotes the rule of law

to a higher status than he is willing to accept. Likewise, Griffith is

sceptical of liberal democracy, as is most commonly embedded in written

constitutions, emphasising as they do individual rights.

The

political constitution can be used as a phrase to describe how the

constitution operates, or as an ideal-type/normative description as to

how governance should operate, with a particular underlying

understanding that the input of the judiciary into matters of governance

should be heavily limited. On the descriptive side, the UK constitution

has often been characterised as a customary constitution, based upon a

pragmatic evolution of the political practice of governance and relying

upon past practice for constitutional direction. Fearing a drift towards

a more heavily legal constitution - even the imposition of a written

constitution - in the late 70s JAG Griffith wrote his seminal article:

‘The Political Constitution’ (1979) 42 Modern Law Review 1,

which argued for the normative superiority of a political

constitution. Griffith argued strongly against a Diceyan interpretation

of the UK constitution, primarily because it promotes the rule of law

to a higher status than he is willing to accept. Likewise, Griffith is

sceptical of liberal democracy, as is most commonly embedded in written

constitutions, emphasising as they do individual rights.There are several ways of interpreting Griffith's work. For instance, one might understand his work as a response to the specific context that he was observing. As the subsequent work of Harlow and Rawlings (Law and Administration (With Richard Rawlings) (Cambridge University Press: 2009) 3rd edition) expands in more detail, there has long been a school of thought which is deeply suspicious of the alleged 'conservative' underpinnings of the judiciary, which in the 20th century meant an anti-welfarist tendency. The courts, in other words, were liable to block socially progressive policies. By contrast, today, the strongest voices against judicial activism tend to suggest that the modern judiciary is too easily tempted towards imposing its interpretations of liberalism. The blocking here is potentially of deeply held cultural beliefs, as best developed and agreed upon by the political process.

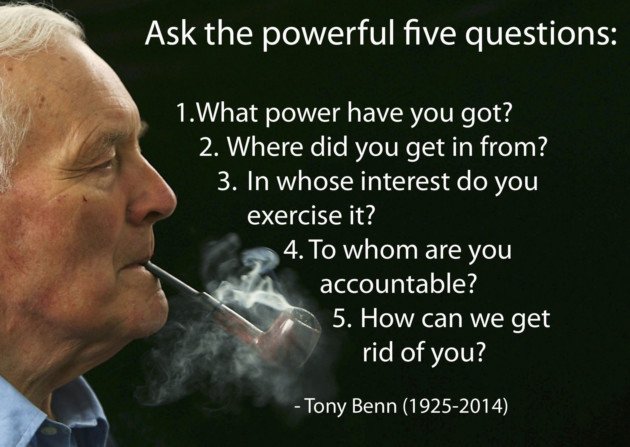

Thus the more powerful argument of proponents of the political constitution is that the law in the courts represents politics by other means and reduces the potential for the electorate, through the Government, to implement its will. As with the famous Tony Benn quote, the most important thing for political constitutionalists is strengthening the processes by which the electorate can both implement and interrogate power, hence the five questions Benn proposes.

Conversely, what this implies is that we should not be squeemish about the political process, but should instead embrace its adversarial nature. To cite Griffith: 'It is arguable that society is in reality in a highly combustible condition. ..... [C]onflict is at the heart of modern society.' (1979, 2) And 'a society is endemically in a state of conflict between warring interest groups, having no consensus or unifying principles sufficiently precise to the basis of a theory of legislation' (19). He later states 'Only political control, politically exercised, can supply the remedy.' (16)

Griffith continued making this argument in his later career, and it has also been taken up with some force by others. Tomkins in his work has taken on the challenge of defending the Westminster Parliament from the charge of being ineffective in the face of strong Executive power (A. Tomkins, ‘In Defence of the Political Constitution’ (2002) 22 OJLS 157; see also Flinders, M. (2010) ‘In defence of politics’ The Political Quarterly, vol. 81, No.3, July-September 2010, pp.309-325). More recent work has worked on developing models within which to understand the balance between political and legal power in the UK Constitution, see Gee and Webber (G. Gee and G.C.N. Webber, ‘What is a Political Constitution?’ (2010) 30 OJLS 273). See also this special edition of the German Law Journal in 2013.

The Political Constitution and Brexit

One of the features of Brexit is that it can be understood as a reaction against a constitutional settlement that for some came to defer too much power to the law and ultimately the courts. Brexit is in other words a shift back towards a more strongly politically based constitution. If so, this places even more emphasis on the inner workings of Parliament to manage the operation of the constitution. In a more recent article Webber has emphasised the importance of the opposition in the constitution ('Loyal Opposition and the Political Constitution' Oxford J Legal Studies (2016)). Put in light of current politics, this is a fascinating point given the current disruption in the internal workings of the post-2010 opposition, the Labour Party.

The role of the courts in the Political Constitution

What then is the rule of law, or the role of the courts, in the political constitution? Tomkins attempted to outline this in: Tomkins, A. (2010) The Role of the Courts in the Political Constitution. University of Toronto Law Journal, 60(1), pp. 1-22. The difficulty is that any concession to the rule of law risks undermining the normative claims for the political constitution once it is conceded that there is some role for the courts in protecting individual rights (see P P Craig, 'Political Constitutionalism and the Judicial Role: A Response' (2011) 9 International Journal of Constitutional Law 112 for a critique of Tomkins' article). This leaves an inherent problem in defining the boundary line of legitimate judicial activity (for instance see this exchange of views: Hale v Stevens), which is sometimes phrased in terms of the duty of the court to show deference to the political branch.

However, there remains a strong body of work which argues: (i) the dangers of a constitution that relies only upon the political branch to secure accountability (eg F.F. Ridley, ‘There Is No British Constitution: A Dangerous Case of the Emperor’s Clothes’ (1988) 41 Parl Aff 340); the power of the legal branch to secure accountability (eg T.R. Hickman, ‘In Defence of the Legal Constitution’ (2005) 55 UTLJ 981); and (ii) the moral necessity of higher order law for the purposes of a functioning constitution (eg Laws, J (Sir), ‘Law and democracy’ [1995] PL 72).

The riposte to this position can be summarised in this quote:

Legal constitutionalists sometimes present the vagaries of ordinary, everyday political life as potentially destructive of the rule of law and individual rights and which, therefore, must be constrained by judicially enforceable constitutional prescriptions. Instead, the normative turn in political constitutionalist writing offers an account of how politics serves as the 'vehicle' through which to realize these same (and other) ends. More particularly, the very aspects of day-to-day political life that 'many legal and political theorists are apt to denigrate - its adversarial and competitive qualities, its use of compromise and majority rule to generate agreement, the role of political parties - are those' that political constitutionalists like Bellamy and Tomkins 'seek to praise'. In doing so, the focus of this ‘turn’ is not on an idealized form of political life, but rather the actual day-to-day political life found in real world constitutions, with all of its imperfections and foibles. (Gee and Webber 2010, 281).

The political constitution v the complex constitution

The modern constitution has not just evolved legal constraints on the exercise of public power, it has also developed a series of other institutional and procedural solutions, a common feature of which has been their independence, or quasi-independence, from direct political oversight (eg Scott, C. (2000) ‘Accountability in the regulatory state’, Journal of Law and Society, 27(1), 38–60). This move towards a complex constitution, with a heavy emphasis on specialisation, has also received significant attack in recent years along similar lines to those expressed against the legal constitution (eg Flinders (2011) ‘Daring to be a Daniel: The Pathology of Politicized Accountability in a Monitory Democracy’ Administration & Society 2011 43: 595).

This debate will be looked at in a later post.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment